Sukhi Lalli does more than dispense pills in his Yates Street store … much, much more

There’s no white lab coat, he doesn’t stand two feet above the crowds peering over a mantel strewn with pill boxes and dispensing equipment and there’s no brand name other than his own moniker plastered on his pharmacy’s front door. And though capable of understanding the hieroglyphics etched onto a prescription slip, Sukhi Lalli is not your typical pharmacist.

There’s no white lab coat, he doesn’t stand two feet above the crowds peering over a mantel strewn with pill boxes and dispensing equipment and there’s no brand name other than his own moniker plastered on his pharmacy’s front door. And though capable of understanding the hieroglyphics etched onto a prescription slip, Sukhi Lalli is not your typical pharmacist.

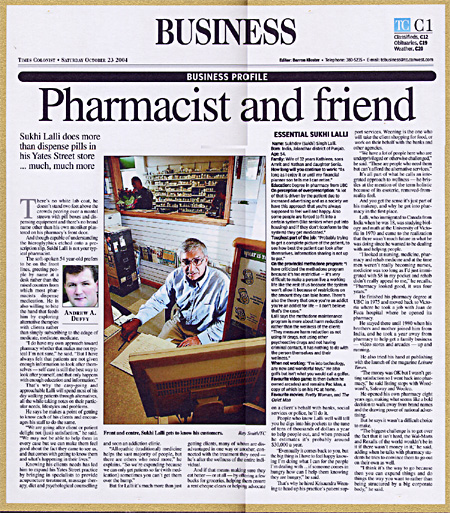

The soft-spoken 54 year-old prefers to be on the front lines, greeting people by name at a desk rather than the raised counters from which most pharmacists dispense medication. He is also willing to bite the hand that feeds him by exploring alternative therapies with clients rather than simply subscribing to the adage of medicate, medicate, medicate.

“I do have my own approach toward pharmacy whether that makes me not typical I’m not sure,” he said. “But I have always felt that patients are not given enough information to look after themselves — self care is still the best way to look after yourself, and that only happens with enough education and information.”

That’s why the easy-going and approachable Lalli will spend most of his day walking patients through alternatives, all the while taking notes on their particular needs, lifestyles and problems. He says he makes a point of getting to know each of his clients and encourages his staff to do the same. “We are going after client or patient delight not (just) satisfaction,” he said. “We may not be able to help them in every case but we can make them feel good about the fact they came to see us, and that comes with getting to know them and what’s happening in their lives.”

Knowing his clients needs has led him to expand his Yates Street practice by bringing in specialists to provide acupuncture treatment, massage therapy, diet and psychological counselling and soon an addiction clinic. “Allopathic (traditional) medicine helps the vast majority of people, but there are others who need more,” he explains. “So we’re expanding because we can only get patients so far (with medication) sometimes you can’t get them over the hump.” But for Lalli it’s much more than just getting clients, many of whom are disadvantaged in one way or another, connected with the treatment they need — he’s after the wellness of the entire individual.

And if that means making sure they eat better — or at all — by offering a few bucks for groceries, helping them ensure a rent cheque clears or helping advocate on a client’s behalf with banks, social services or police, he’ll do it. People who know Lalli well will tell you he digs into his pockets to the tune of tens of thousands of dollars a year to help people out, and when pressed he estimates it’s probably around $30,000 a year. “Eventually it comes back to you, but the big thing is I have to feel happy knowing I’m doing what I can for the people I’m dealing with … if someone comes in hungry how can I help them knowing they are hungry,” he said. That’s why he hired Krisaundra Weening to head up his practice’s Patient Support Services. Weening is the one who will take the client shopping for food, or work on their behalf with the banks and other agencies. “We have a lot of people here who are underprivileged or otherwise challenged,” he said. “These are people who need them but can’t afford the alternative services.” It’s all part of what he calls an integrated approach to wellness — he bristles at the mention of the term holistic because of its esoteric, removed-from-reality feel. And you get the sense it’s just part of his makeup, and why he got into pharmacy in the first place.

Lalli, who immigrated to Canada from India when he was 18, was studying biology and math at the University of Victoria in 1970 and came to the realization that there wasn’t much future in what he was doing since he wanted to be dealing with and helping people. “I looked at nursing, medicine, pharmacy and rehab medicine and at the time men weren’t really becoming nurses, medicine was too long as I’d just immigrated with $8 in my pocket and rehab didn’t really appeal to me,” he recalls. “Pharmacy looked good, it was four years.”

He finished his pharmacy degree at UBC in 1975 and moved back to Victoria where he took a job with Juan de Fuca hospital where he opened its pharmacy. He stayed there until 1980 when his brothers and mother joined him from India, and he took a year away from pharmacy to help get a family business — video stores and arcades — up and running. He also tried his hand at publishing with the launch of the magazine Leisure Times. “The money was OK but I wasn’t getting satisfaction so I went back into pharmacy,” he said listing stops with Woodward’s, Safeway and Woolco. He opened his own pharmacy eight years ago, making what seems like a bold decision to walk away from brand names and the drawing power of national advertising. But he says it wasn’t a difficult choice to make. “The biggest challenge is to get over the fact that it isn’t hard, the Wal-Marts and Rexalls of the world wouldn’t be in it if there wasn’t money in it,” he said, adding when he talks with pharmacy students he tries to convince them to go out on their own as well. “I think it’s the way to go because then you can expand things and do things the way you want to rather than being structured by a big corporate body,”he said.

ESSENTIAL SUKHI LALLI

Name: Sukhdev (Sukhi) Singh Lalli.

Born: India, Jalandhar district of Punjab.

Age: 54.

Family: Wife of 32 years Kathleen, sons Amrit and Nathan and daughter Sonia.

How long will you continue to work: “As long as I enjoy it or until my financial planner son tells me I can retire.”

Education: Degree in pharmacy from UBC

On perception of overprescription: “A lot of that is driven by the patient due to increased advertising and as a society we have this approach that you’re always supposed to feel well and happy. Also some people are forced to fit into a certain system (like seniors when put into housing) and if they don’t (conform to the system) they get medicated.”

Toughest part of the job: “Probably trying to get a complete picture of the patient, to see how best the patient can look after themselves. Information sharing is not up to par.”

On the provincial methadone program: “I have criticized the methadone program because it’s too restrictive — it’s very difficult to make a person live a working life like the rest of us because the system won’t allow it because of restrictions on the amount they can take home. There’s also the theory that once you’re an addict you’re an addict for life — I don’t believe..

Saheb